Over the last several weeks, we have been discussing the subject of CHF (congestive heart failure). I discussed the differences between heart failure from systolic dysfunction (problems with the heart contracting/pumping) and problems caused by diastolic dysfunction (problems during the relaxation phase of the cardiac cycle). These are clinical syndromes and are brought on by a variety of conditions, some of which we touched upon at the time. I used the term cardiomyopathy in the first of those blogs and would like to delve more deeply now into what that means. Cardiomyopathy (Latin for “sickness of the heart muscle”) refers to structural abnormalities that can affect both mechanical and electrical function of the heart. People with a cardiomyopathy can have CHF, but sometimes a cardiomyopathy is asymptomatic, while in other situations the problems are not specifically related to CHF.

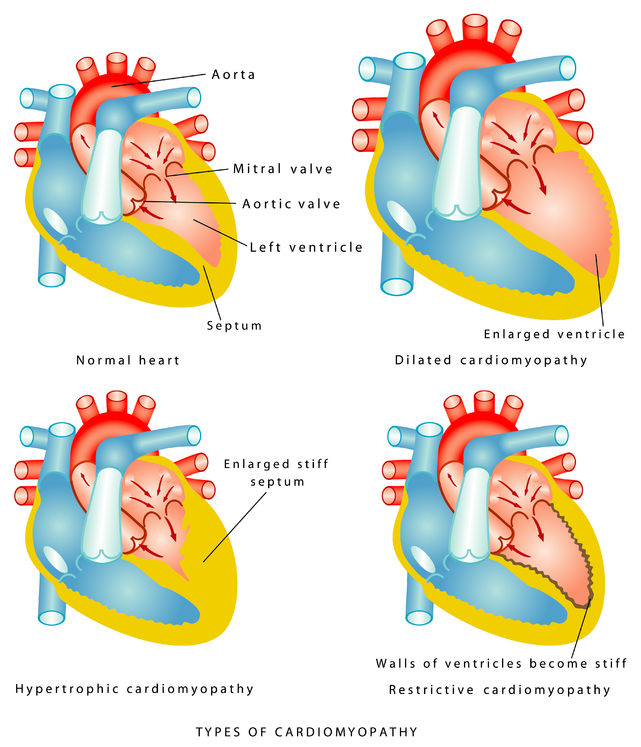

As the diagram below shows, cardiomyopathies have traditionally been divided into three categories: dilated, hypertrophic and restrictive.

Dilated cardiomyopathies are virtually always associated with systolic dysfunction, where the heart pumping function is diminished. There are many causes of dilated cardiomyopathies, including coronary artery disease (“ischemic cardiomyopathy”), untreated valvular heart disease (particularly caused by aortic and mitral regurgitation), myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), complications of pregnancy (“peripartum cardiomyopathy”), drugs (most commonly from certain cancer drugs), alcohol (“alcoholic cardiomyopathy”), infections (Chagas disease—caused by a parasite native to many Latin American countries), accentuated adrenaline states (seen with chronic cocaine use, hyperthyroidism, and pheochromocytoma—a tumor that makes too much adrenaline), and idiopathic (the doctor can’t find a specific cause). Many cases of idiopathic cardiomyopathy are likely genetic, where cardiomyopathy runs in families.

Some aspects of the treatment of all these cardiomyopathies are the same—e.g., beta blockers and blockers of the renin-angiotensin system (ACE inhibitors and ARBs), which we discussed in an April blog “Succeeding with Heart Failure.” Some of the treatments are unique to the particular condition. For instance, we often perform stenting or bypass surgery in patients with an ischemic cardiomyopathy, or valve replacement in patients with a cardiomyopathy brought on by valvular heart disease. We stop the offending drug (or cocaine or alcohol) in cases where these agents are implicated. We treat an infection if that is the cause. And we have treatment for an overactive thyroid, or can remove the tumor in patients with pheochromocytoma.

In the next couple weeks, I’ll discuss the other two categories of cardiomyopathy: hypertrophic and restrictive.

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC