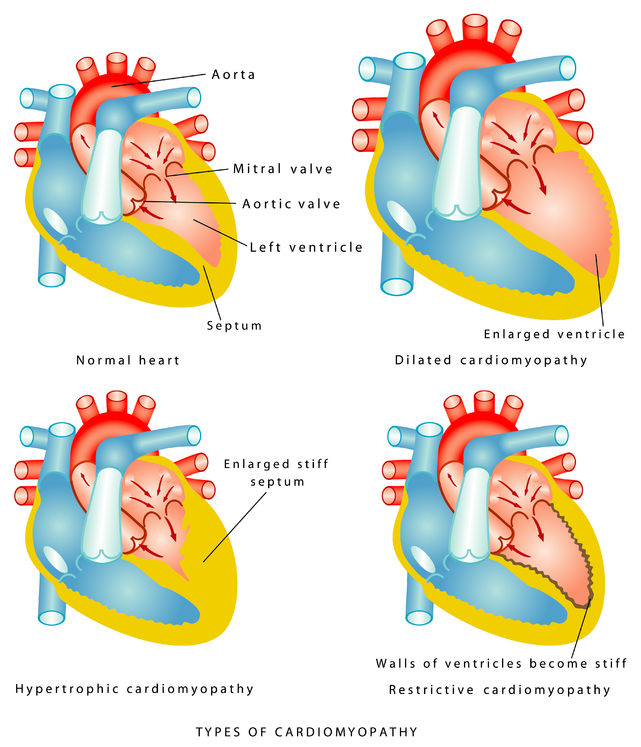

Last week we discussed what a cardiomyopathy is, including the three categories of dilated, hypertrophic and restrictive. We then focused on types of dilated cardiomyopathies, along with some discussion about their treatment. Today I’ll continue our review of cardiomyopathies by focusing on hypertrophic.

Whereas a dilated cardiomyopathy is defined by the heart chamber being enlarged, a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is defined by the heart muscle being abnormally thick, in the absence of a known stimulus to thickening, such as hypertension or aortic stenosis. These cardiomyopathies are virtually always on a genetic basis and many of the mutations (variations of a gene from what is generally seen in people) for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have been detected. But new ones are constantly being discovered.

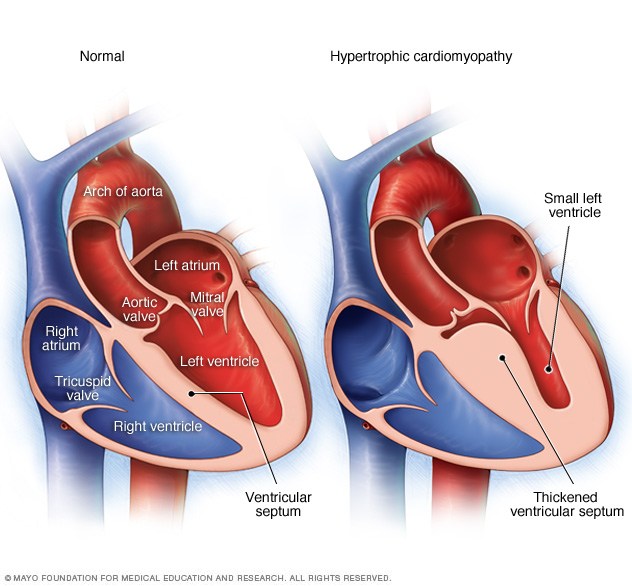

While the thickened heart muscle of a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy usually leads to the heart function being unusually strong, this is not necessarily a good thing. Several problems can arise in this condition. The heart may contract so vigorously that it can suck one or both mitral valve leaflets toward the thickened heart muscle (see image below) and physically block the outflow of blood as it starts to exit the aortic valve in the area we call the left ventricular outflow tract (abbreviated “LVOT”). We term this hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, abbreviated “HOCM.” This can lead to a drop in blood pressure, dizziness, and shortness of breath.

Furthermore, the thickened heart muscle is abnormally stiff, and the heart doesn’t relax as easily, leading to fluid retention to improve filling of the heart with blood (remember the “slingshot” effect that fluid retention can provide, which we discussed in an earlier blog). But fluid retention can cause shortness of breath. Often, patients can experience angina (chest pain from insufficient blood flow) due to the number of blood vessels in the heart muscle not being sufficient for the large heart muscle mass. Finally, the muscle fibers of the thickened heart are not organized as well as in a normal heart, often running crisscross rather than in parallel. This leads to electrical instability, creating a situation where life-threatening heart rhythms can occur.

Treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies from person to person, as people can experience a wide range of symptoms—from mild shortness of breath, angina or dizziness, to fainting and cardiac arrest. Many people have no symptoms at all, and we focus on assessing their risk of dying suddenly from an arrhythmia. The first line of treatment for symptomatic patients is beta blockers, a category of medications we’ve discussed previously. They slow the heart rate, giving the heart more time to fill with blood, and they decrease the strength of the heart contraction, lessening the tendency for there to be outflow tract obstruction and angina.

Diuretics (“water pills”) are often used to remove excess fluid, but it can be very difficult to pick the correct dose, as dehydration leads to a worsening of LVOT obstruction. We try to assess a person’s tendency to life-threatening heart rhythms through stress tests and monitoring. Also, people with relatives who have died suddenly are at greater risk themselves, as it likely means that they have inherited a high-risk gene mutation. In people we consider to be at high-risk—and certainly in people who have already survived a cardiac arrest—we implant a defibrillator (aka an “ICD”). Other treatments include reduction of the muscle mass through surgery or catheter procedures using alcohol to “ablate” the septal muscle tissue.

A new medication, called mavacamten, has been developed and works by directly inhibiting the molecular structures in the muscle fibers that lead to force generation, thus decreasing the over-vigorous contraction that is the hallmark of HOCM. It has recently been approved and is now available for use.

One of the paradoxical things about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is that it is more ominous when it is discovered in younger people, particularly in adolescents. We have all heard of the tragic stories where elite athletes have died at a young age from this condition. The likely explanation of this observation is that people who aren’t discovered to have this disease until later in life are likely to have a more benign form, which has allowed them to survive well into adulthood without any dangerous events.

We are constantly learning more about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and many of the referral centers around the country do sophisticated genetic testing to risk stratify patients and help to target therapy.

Next week we’ll complete our discussion of cardiomyopathies with a look at the restrictive category.

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC