We’ve spent a lot of time discussing atrial fibrillation these past few weeks—and with good reason. Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia that requires treatment, and it accounts for numerous visits to cardiologists’ offices and emergency rooms. But the atria can misfire in other ways, too.

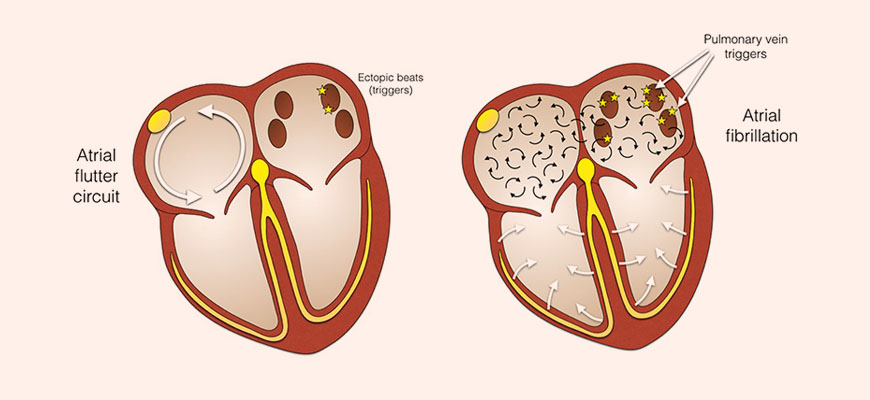

Often lumped together with atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter is also a fast heart rhythm arising in the atria, more specifically in the right atrium. The frequency is somewhat slower than atrial fibrillation, with the flutter waves occurring at around 300 bpm. This is slow enough that one can usually see a more organized pattern on the EKG, often a so-called “sawtooth” wave pattern noted in certain EKG leads. Like atrial fibrillation, it can lead to a fast ventricular rate, and it carries an elevated risk of stroke. We use the same criteria for anticoagulation in patients with atrial flutter as we do for atrial fibrillation.

We also treat the two arrhythmias similarly, utilizing a few strategies. First, we evaluate the heart to assess why it is in an abnormal rhythm. Our questions focus on a history of hypertension, valvular heart disease, CHF, alcohol intake, thyroid disorders, and lung disease, all of which enhance the likelihood of having these arrhythmias. We almost always perform an echocardiogram to assess the heart function, size, valves and pressures.

Second, we try to control the rate by using medications that block the AV node (discussed in a previous blog). Medications that do this include beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and digoxin (the latter used less frequently because it isn’t as effective as the other drugs). Third, we try to maintain normal sinus rhythm (NSR). Certain types of antiarrhythmic drugs (flecainide and amiodarone are two commonly used examples) can be utilized to prevent recurrences of atrial fibrillation or flutter and sometimes even convert a person back to NSR. There are pros and cons of using these more potent medications, though, as they sometimes have dangerous side effects.

Often, we need to use an electrical shock to return the patient’s rhythm to normal—we call this electrical cardioversion. Since it is rarely an emergency, we take the time to put the person to sleep first, and then give a jolt of electricity, successfully restoring NSR about 80-90% of the time. However, atrial fibrillation or flutter can recur—days, weeks or months later; but sometimes after only a few minutes or hours.

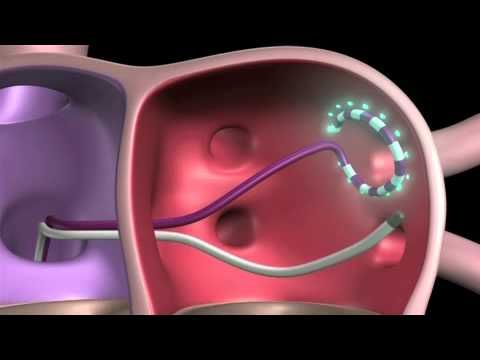

One option—in addition to medication—to prevent atrial fibrillation or flutter is to have an ablation. For atrial flutter, the abnormal circuit is in the right atrium and a particular pathway can be electrically seared with a special catheter in order to create a scar and stop the electricity from going through the pathway. Atrial fibrillation ablation is performed in the left atrium and is more complex, so the success rate is not as high—about 60-70% instead of 90% for atrial flutter ablation. Below are some graphics that illustrate atrial flutter and fibrillation, as well as an ablation catheter.

Everybody experiences atrial fibrillation and flutter somewhat differently, so the treatment must be individualized for each person and depends on how fast their heart rate is, how symptomatic they are, how they tolerate and respond to various medications, and what their underlying heart issues may be. Treating atrial fibrillation and flutter is a complex process and requires a collaborative approach between physician and patient. One size doesn’t fit all!

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC