Last week we introduced the concept of valvular heart disease, starting with a discussion of how valves in the heart work, and then touching briefly on how they malfunction. Today we’ll be talking about one of the most common forms of valvular dysfunction: aortic stenosis (generally abbreviated “AS”).

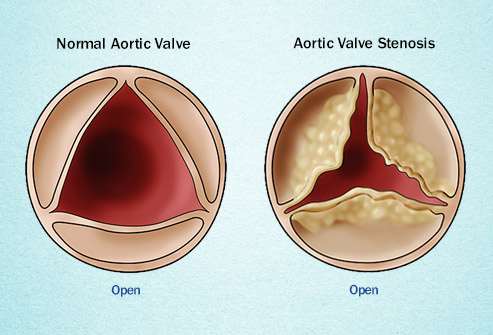

AS is increasingly prevalent as we age, though it is not by any means an invariable development. The normal aortic valve has three leaflets or “cusps.” Over time, the leaflets can thicken and develop calcium deposits that limit their mobility. Thickening, by itself, is referred to as aortosclerosis (Greek for “hardening of the aortic valve”). As the leaflets become stiffer, stenosis develops, where the opening for the blood to exit the heart into the aorta becomes smaller. This narrowed opening can be mild, moderate, or severe. It is in the last category that the heart starts to feel the strain of the narrowed orifice. The extra work the heart must perform can lead to chest pain, shortness of breath, and sometimes fainting. With more extreme compromise, a person can have a heart attack, develop congestive heart failure or even sudden death.

The development of AS generally doesn’t happen until after the age of 65 or so. However, some people are born with only two aortic leaflets and have what we call a bicuspid aortic valve. These valves age more quickly, and patients sometimes develop severe AS in their 50s and early 60s (rarely even in their 40s). There is no known medical therapy for AS, meaning no medications that help open the valve or reverse the process of thickening and calcification. So, traditionally, when a person developed symptoms of severe AS—whether it was chest pain or pressure, shortness of breath, or fainting—open heart surgery to replace the valve was the only option. This operation involves opening the chest and cutting out the old valve and then putting in a new one—either bioprosthetic (biologic—generally from a cow, a pig, or a human cadaver), or a mechanical valve. The advantage of the latter is that it is more durable and generally lasts longer, putting off the need for a reoperation for as many as 25 years or more. The disadvantage is that a person needs to be anticoagulated with warfarin for the rest of his or her life.

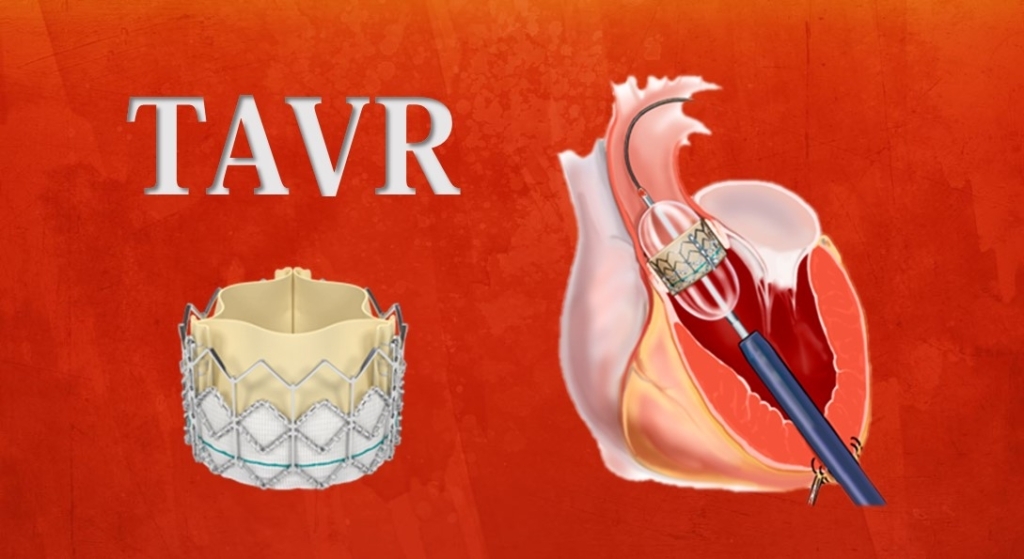

In the last several years, though, there is another option for patients with severe AS: TAVR (transcutaneous aortic valve replacement), where a bioprosthetic valve is delivered into the aorta through a catheter placed through the groin (or, less commonly, across the chest wall) and “deployed” inside the old diseased valve during balloon inflation there. While it is still a complicated procedure that carries some risk, it is generally safer than an open-heart operation and has become the procedure of choice in the elderly or in people with serious medical conditions like COPD that make surgery much riskier. In fact, we are now utilizing this less invasive procedure for replacing the aortic valve in moderate risk patients.

Thus, while AS can be a life-threatening problem, it is curable with valve replacement. And now that TAVR is available, more people are candidates for this life-saving procedure.

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC