Most people have heard of an “irregularity” in the heart rhythm or having an arrhythmia. But there are several types of irregularities and arrhythmias. Many arrhythmias are benign, but some require treatment. So, knowing you have an arrhythmia is not the end of the subject—it is important to know what type of arrhythmia it is.

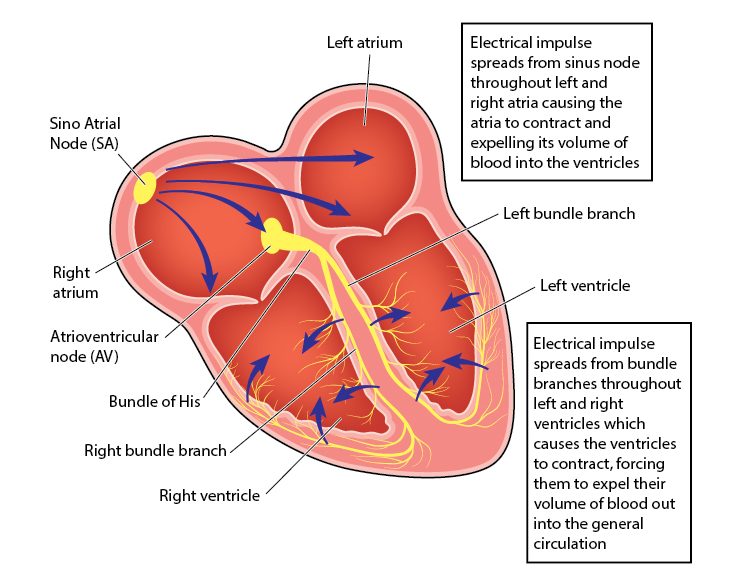

We use the term normal sinus rhythm (abbreviated NSR) to refer to the normal electrical pattern of the heart. The meaning of “normal” is pretty self-evident. “Sinus” refers to the particular location in the right atrium (upper chamber of the right heart) called the sinus node or sinoatrial node (abbreviated SA node), which serves as the heart’s natural pacemaker. In actuality, much of the heart tissue can initiate its own electrical impulses and take over the heart rhythm. However, the sinus node tends to have a faster natural rate of firing (generating electrical impulses), so it drives the heart rhythm. Its natural rate is about 50-100 beats per minute (bpm).

From the sinus node, the impulse travels through the rest of the right atrium, over to the left atrium and also down to a gateway we call the atrioventricular node (abbreviated AV node) and into the ventricles (the main pumping chambers) through the Bundle of His. The ventricles have specialized conduction tissue called bundle branches (a right and a left, the latter divided into an anterior and a posterior portion). Of note, slow conduction in these conduction pathways leads to different patterns on the EKG, such as left and right bundle branch blocks (abbreviated, respectively, LBBB and RBBB). These blocks don’t mean the same thing as blockages in the arteries—they are electrical blockages or slowed conduction. Below is a schematic of the heart’s conduction system.

An arrhythmia means only that the heart rhythm is not normal, not NSR—and there are dozens of ways that the heart rhythm can be abnormal. It can be too slow (bradycardia) or too fast (tachycardia). One of the causes of bradycardia can be when the electrical impulses fail to reach the ventricle, a problem we refer to as heart block. And there are many types of tachycardia: both atrial (another part of the atrial tissue outside the sinus node becomes the drum major and beats too fast) and ventricular (the ventricle becomes the drum major and beats too fast). There are several mechanisms by which each of these can happen, too.

The heart can fibrillate, whereby the electrical pulses come so fast that the muscle can’t keep up with the electricity and just quivers. If the ventricles fibrillate, it is lethal within seconds, as the main pumping chambers are no longer beating. If the atria fibrillate, it is not lethal, as the ventricles are still pumping—only the atria are fibrillating.

Furthermore, we can have premature beats—electrical impulses that come earlier than expected—arising either from the atria (premature atrial complexes or PACs) or from the ventricle (premature ventricular complexes or PVCs). We often call these “extra beats,” though they generally aren’t “extra,” but replace the beat that would have come a split second later. Interestingly, when we take our pulse (or the blood pressure cuff does), we often can’t feel these premature beats, which is why we think we have missed a beat—thus the term “skipped beat.” Because the impulse has come early, the heart hasn’t had enough time to completely fill with blood and doesn’t generate much “oomph,” leading to a weak or undetectable heartbeat. Almost everybody has PACs and PVCs, some people more frequently than others. Generally, these are benign, but rarely they can be a sign of cardiac strain.

Premature beats, because they create a break in the regularity of the pulse, lead us to describe the heart rhythm as “irregular.” Not all arrhythmias are irregular. For instance, sinus bradycardia and atrial tachycardia are generally perfectly regular. But many arrhythmias are irregular—heart block often is, as is atrial fibrillation.

Now you know that there are multiple types of arrhythmias and that some of these are irregular. Not all of these are dangerous or even clinically important. But we will return to a very clinically significant arrhythmia next week: atrial fibrillation.

Greg Koshkarian, MD, FACC